02 02 2022 | by Victor Xing | Capital Markets

All articles 6

08 26 2019 | by Victor Xing | Economics

Prolonged stimulus paves way for wealth redistribution

05 20 2018 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks

Alternative narrative on the natural rate of interest

01 07 2018 | by Victor Xing | Capital Markets

Flatter yield curve a symptom of ineffective tightening

12 04 2017 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks

Bond market term premium and wolves of Yellowstone

09 20 2017 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks

QE’s distributional effects a rising political liability

12 04 2017 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks

Bond market term premium and wolves of Yellowstone

Bond market term premium and wolves of Yellowstone

- Ashwin Alankar of Janus Henderson articulated a view that central bank induced term premium suppression is akin to the killing of wolves in Yellowstone that fueled the overpopulation of elks, and the subsequent overgrazing which decimated the ecosystem is similar to present day’s rise in market distortions and vulnerability to volatility

- While we agree with Alankar that bringing back bond market term premium would restore balance to the financial system, the ineffectiveness of using rate hikes to push up term premium is evident by the on-going curve flattening

- Monetary authorities acknowledged rate cuts’ ineffectiveness at pushing down term premium during the financial crisis, but fears of “market tantrum” induced cognitive dissonance to argue that rate hikes are effective in reverse

- Rate hikes are akin to the failed policy of trapping and relocating elks in hopes of containing overgrazing, and the current policy path will continue to fuel non-bank risk-taking and further erode markets’ ability to brace for shocks

Term premium as a safeguard against market excess

Ashwin Alankar of Janus Henderson published his latest article “Brace for Steeper Yield Curves as the Wolves Return,” which highlighted grey wolf’s role in maintaining a delicate balance in Yellowstone’s ecosystem by keeping population of herbivores in-check, which in-turn reduced risks of overgrazing of young brush and trees in the park. The U.S. Nation Park Service once believed the “picturesque” scene of roaming elks and other “peaceful” animals would represent an ideal environment for visitors, nearby ranchers and farmers, but the hidden costs of removing organic risk from the environment soon became apparent:

“Once the wolves were gone, the elk population exploded and they grazed their way across the landscape killing young brush and trees. As early as the 1930s, scientists were alarmed by the degradation and were worried about erosion and plants dying off.”

Short-term rates have limited efficacy toward term premium

While higher term premium (thus a steeper Treasury curve) would bring back volatility, we believe conventional rate hikes would do little to push up term premium, thus we disagree with Alankar on his following point:

“However, over the past month, yields on two-year Treasuries have moved up about 40 basis points to their highest since 2008 on expectations of further Fed rate increases. Just as ultra-low rates drove down volatility, the same economic forces of substitution should work in reverse, lifting volatility as rates normalize and investors move away from selling volatility. Risk will return and with it the term premium.”

Short-term rates have limited efficacy in affecting term premium in recent decades amid unconventional easing:

- As observed during “Greenspan’s Conundrum,” soaring front-end rates was easily offset by BOJ’s initial QE

- Higher short-term rates is akin to removing small populations of elk without fundamental macro impacts

- The QE programs that kept “wolves of financial markets” at bay are continuing to dampen realized volatility

Similar to U.S. National Park Service officials’ prior preference for peaceful herds of elks and an absence of “risky animals,” some monetary policymakers maintained a bias against market volatility, and they perceive removal of “unwanted volatility” as beneficial to financial markets to inadvertently reduced markets’ risk tolerance. Additionally, policymakers had previously acknowledged rate cuts’ ineffectiveness at pushing down term premium at the start of Great Recession, but “tantrum fears” had subsequently fueled “policy cognitive dissonance” to argue otherwise during policy normalization.

BIS’s latest quarterly review also argued that higher short-term bond yields have consistently failed to lift term premium nor dampen risk-parity flows in recent years:

“The evolution of the term premium underlies the different market outcomes across tightening episodes. A decomposition of 10-year US Treasury yields into a future rate expectations component and a term premium suggests that declining term premia drove long-term rates lower both now and during the mid-2000s “conundrum” episode. In both cases, the drop in estimated term premia more than offset the upward revision in expectations about the future path of short-term interest rates”

If officials dislike wolves but still want to have demonstrate “the courage to act,” then relocating elks (or in the case of financial markets, pushing up short-term rates) would be seen as a “policymakers acted” response.

The absence of wolves can hurt elks over the long-term

While some investors view monetary policymakers’ aversion toward market jitters (preference to maintain an “anti-wolf” policy) as bullish risk and argued for continued bearishness toward volatility, the experience in Yellowstone would serve as a counter-argument that prolonged “risk suppression” would only breed complacency. Following the reintroduction of wolves, each wolf was averaging 22 elk kills per year, far exceeded the 12 elk per wolf projection as the existing herds were not prepared for the “sudden appearance” of the century-old apex predator after decades of tranquility.

Similar to the Yellowstone experience, investors are increasingly forgoing risk-hedging in broader asset markets following years of policy-led volatility dampening, and the BIS highlighted the following in regards to signs of market complacency:

“High dividends per share were also supported by stock repurchases. Except for a short interlude in 2008-09, share repurchases have been very large since the early 2000s. When and if interest rates begin to rise, corporates may have the incentive to tilt their capital structure back to equity, or at least to reduce stock repurchases, which could raise further questions about stock market valuations.”

“If net income continued growing at this more modest pace, in lockstep with nominal GDP, corporations would not be able to continue growing dividends at current rates while keeping payout ratios constant.”

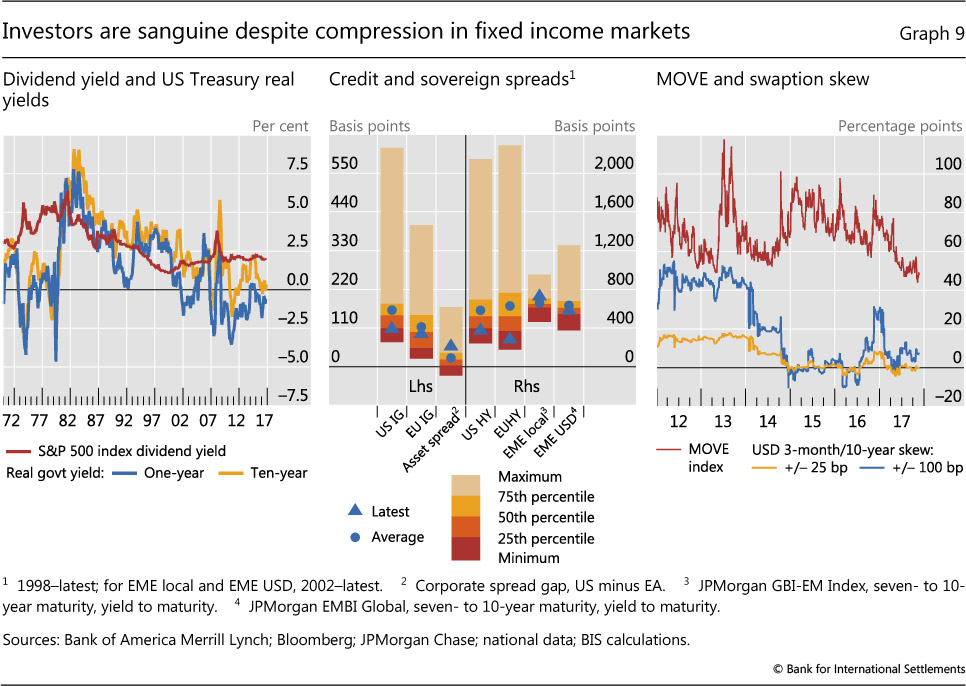

“Stock market valuations looked far less frothy when compared with bond yields. Over the last 50 years, the real one- and 10-year Treasury yields have fluctuated around the dividend yield (Graph 9, left-hand panel).”

“In spite of these considerations, bond investors remained sanguine. The MOVE index suggested that US Treasury volatility was expected to be very low, while the flat swaption skew for the 10-year Treasury note denoted a low demand to hedge higher interest rate risks, even on the eve of the inception of the Fed’s balance sheet normalization (Graph 9, right-hand panel). That may leave investors ill-positioned to face unexpected increases in bond yields.”

Given the above, it is reasonable to argue that even a small scale volatility shock would likely induce heightened market reaction, even if the event merely reverses some of the term premium compression in the sovereign bond markets. Given markets’ exposure to risk-parity positions, damage to non-bank financial institutions’ balance sheets will be notable.

Furthermore, as the extirpation of wolves exposed policymakers to previously unanticipated macro risks, the suppression of known market volatility via term premium dampening also implies the next wave of risk contagion will likely come from unconventional sources beyond the current regulatory focus (similar to the lack of “dot-com euphoria” led some investors to see that there was no market excess prior to the GFC), and a “well sheltered” financial market would be ill-prepared to adapt.

Thus, if the status quo persists, the likely scenarios are not whether there will be volatility, but whether policymakers would choose to let markets face a rise in known volatility catalysts (rise in term premium, lower risk asset valuation), or to continue the current “hand-holding” until an unconventional risk threatens a brittle financial system with policymakers caught off-guard.

Disclaimer: not investment advice.

Next article09 20 2017 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks