02 02 2022 | by Victor Xing | Capital Markets

All articles 6

08 26 2019 | by Victor Xing | Economics

Prolonged stimulus paves way for wealth redistribution

05 20 2018 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks

Alternative narrative on the natural rate of interest

01 07 2018 | by Victor Xing | Capital Markets

Flatter yield curve a symptom of ineffective tightening

12 04 2017 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks

Bond market term premium and wolves of Yellowstone

09 20 2017 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks

QE’s distributional effects a rising political liability

01 07 2018 | by Victor Xing | Capital Markets

Flatter yield curve a symptom of ineffective tightening

Executive Summary

- A flattening yield curve highlights Federal Reserve rate hikes’ inability to tighten financial conditions, as low long-term interest rates continued to induce institutional investors to “reach for yield” by moving up the risk ladder

- Central banks initiating “short volatility positions” via QE have dampened long-term sovereign bond yields, which crowded out private capital and induced investors to “find something else to do” by buying more esoteric assets

- A flat yield curve alone would only pave the way, rather than directly trigger events that result in recession, as persistently low long-term bond yields increase the probability and magnify the impacts of balance sheet crises

- Prolonged easy financial conditions as a result of ineffective tightening is not cost-less, for uneven wage growth and rapid asset price appreciation have exacerbated inequality to heighten financial, social and political instability

Policy tightening failed to impact funding conditions

Measures of financial conditions, generally interpreted as effects of monetary policy on the real economy via channels such as exchange rate, short-term and long-term bond yields, stock valuation, and credit spreads, have loosened to peak dot-com bubble levels. This development came despite a steady rise in short-term interest rates as investors priced-in another 2¼ hikes by the end of 2018 thanks to optimism among FOMC participants.

As seen in prior cycles, changes in short-term interest rates alone had yielded little effect on financial conditions, as buoyant risk sentiment strengthened equities, corporate bonds, as well as various forms of “esoteric” investments. This led to debates among policymakers on whether the Fed should hasten the pace of tightening, which further exacerbated pressure on short-term Treasury yields while leaving long-term rates largely unchanged – hence a flatter yield curve.

Despite talks of a steeper rate path, post-crisis financial and policy developments have reduced short-term rates’ impact on broader financial conditions. Plentiful non-bank funding have shifted credit demand away from commercial loans and depressed bank-loan growth. In its place, a ballooning credit market with record (and longer maturity) issuance became the “new normal.” It would make sense for business entities to “borrow for longer” with private capital crowded out by central banks now clamor for long-term cash flows, and this dynamic has tightened credit spreads to record narrow levels.

Central banks’ “short volatility position” pushed investors to “find something else to do”

Former Fed Governor Stein have long argued that unconventional programs (QE) would depressed risk-free returns and induce financial institutions to “take added risk” in an effort to “reach for yield.” His former colleague and incoming Federal Reserve Chair Powell also expressed a similar view, calling Fed’s balance sheet expansion tantamount to “short volatility position,” and private capital displaced by Fed’s outsized presence would “find something else to do,” such as adding duration, credit and liquidity risk with implicit understanding that the central bank “will be there to prevent serious losses:”

“Second, I think we are actually at a point of encouraging risk-taking, and that should give us pause. Investors really do understand now that we will be there to prevent serious losses. It is not that it is easy for them to make money but that they have every incentive to take more risk, and they are doing so. Meanwhile, we look like we are blowing a fixed-income duration bubble right across the credit spectrum that will result in big losses when rates come up down the road. You can almost say that that is our strategy.”

“Right now, we are buying the market, effectively, and private capital will begin to leave that activity and find something else to do. So when it is time for us to sell, or even to stop buying, the response could be quite strong; there is every reason to expect a strong response. So there are a couple of ways to look at it. It is about $1.2 trillion in sales; you take 60 months, you get about $20 billion a month. That is a very doable thing, it sounds like, in a market where the norm by the middle of next year is $80 billion a month. Another way to look at it, though, is that it’s not so much the sale, the duration; it’s also unloading our short volatility position.”

Thus, central banks buying long-maturity debt via reserve creation (“money printing”) would lead to the following:

- Lower long-term bond yields as a result of policy-induced term premium and volatility suppression

- Asset price appreciation (long bonds, equities, corporate debt, etc) as investors react to low volatility

- Decline in bond yields as a result of official demand beget further buying by yield-seeking investors

- Plentiful excess liquidity would strengthen risk assets and further depress interest rates (bullish risk-parity)

Therefore, subdued long-term interest rates is both a catalyst for better risk sentiment as well as a consequence of central bank balance sheet expansion (namely ECB QE), which is in itself bullish risk. It would be no mystery that a flatter yield curve would do little to tighten financial conditions and remain correlated to the “QE trade.”

Flatter yield curve to prolong market excess and heighten systemic risks

Prolonged curve flattening from the aforementioned easy financial conditions (low long-term rates) despite rising short-term rates would steadily increase institutions’ vulnerability to potential balance sheet shocks, as investors continue to add low quality and illiquid assets to “enhance returns.” While this alone would not trigger a recession, willingness to warehouse risks highlight growing complacency, which previously pave the way for balance sheet contagion risks in 2008.

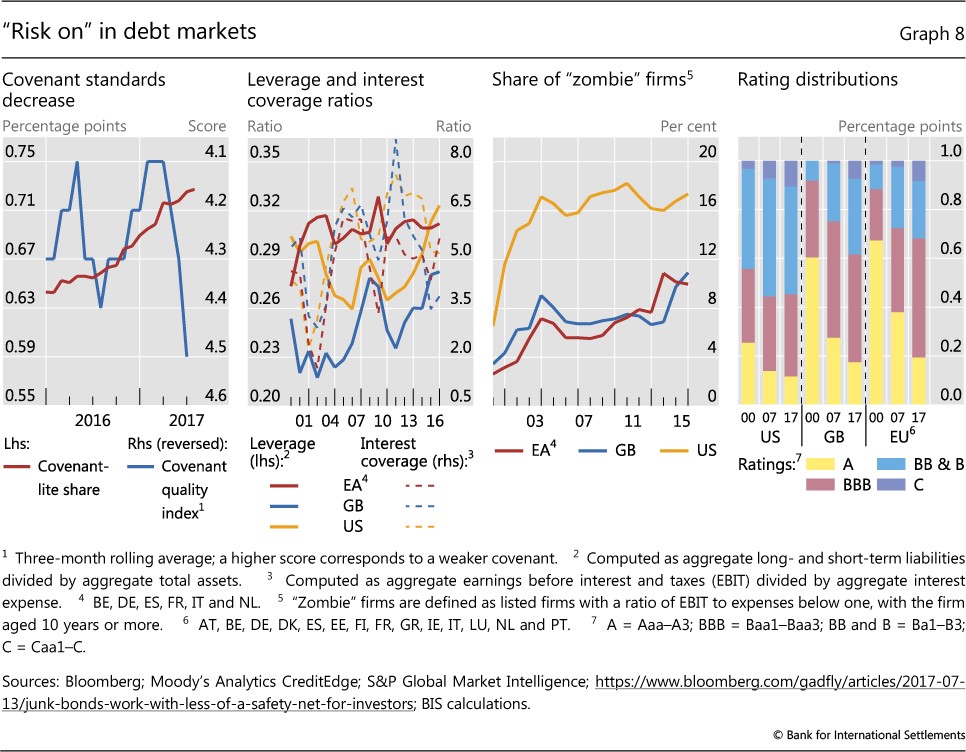

Despite consensus optimism, non-bank financial institutions’ appetite for corporate debt is being cited as a source of risk by more prudent institutions. BIS recently highlighted steady decline in covenant standards, rising leverage, growing share of “zombie” firms, as well as a deterioration in debt rating distributions in its September 2017 quarterly review:

“There were also some signs of search for yield in debt markets, as issuance volumes of leveraged loans and high-yield bonds rose while covenant standards eased. The global volume of outstanding leveraged loans, as recorded by S&P Global Market Intelligence, reached new highs (above $1 trillion). At the same time, the share of issues with covenant-lite features increased to nearly 75% from 65% a year earlier.”

These market developments support a thesis that financial excess would rise in lock-step with the length of curve flattening (ineffective tightening), and the Fed would be unknowingly falling behind the curve to heighten stability risks.

ECB policies outweighed Fed measures to ease global financial conditions

In her July and October 2017 policy speeches, Fed Governor Brainard noted long-maturity Treasuries and long-term European sovereign bonds are “close substitutes,” and foreign central bank policies have held down term premia globally:

“Finally, in circumstances where a major central bank is continuing to expand its balance sheet or maintaining a large balance sheet over a sustained period, this policy would likely exert downward pressure on term premiums around the globe, especially in those foreign economies whose bonds were perceived as close substitutes. Indeed, until very recently, it had been notable how little long yields moved up in the United States even as discussions of balance sheet normalization have moved to the forefront.”

“In any case, recent Federal Reserve staff analysis suggests that cross-border spillovers have increased notably since the crisis and are quite large. For instance, European Central Bank policy news that leads to a 10 basis point decrease in the German 10-year term premium is associated with a roughly 5 basis point decrease in the U.S. 10-year term premium; by contrast, these spillovers were smaller in the years leading up to the crisis.”

Some would argue that by acting cautiously on balance sheet normalization (without actively countering impacts of ECB policy measures), Fed policymakers have partially ceded control of financial conditions to foreign monetary authorities, but the same can be said about other central banks as well, for long-term rates are correlated among advanced economies.

Curve steepener as a bullish volatility expression

Given term premium suppression (via QE) reduced volatility and induced investors to buy risky assets to boost returns, a sustained rise in long-term interest rates would give investors more options to achieve yield targets, thus making risk assets appear less attractive and ultimately erode demands for yield and tighten financial conditions.

Therefore, curve flattener reflects the consensus bearish volatility view where asset prices continue to boom under policy accommodation, while curve steepener expresses a bullish volatility thesis where higher term premium (as a result of “quantitative tightening”) would reverse policy-induced private capital displacement and “financial adventurism.”

Prolonged easy financial conditions carry far-reaching costs

Some policymakers argued that there would be little harm to allow financial conditions to ease continuously, as buoyant asset markets would induce wealth effect and sustain a “Goldilocks” economy. Unfortunately, high asset prices and rising services inflation are already burdening young workers faced with stagnant wage growth to fuel political instability. While some investors insisted that “the people who matter are doing fine,” others such as Allianz’ El-Erian sees otherwise:

“When a sophisticated market economy like the one we have in advanced countries grows for a very long time at a slow pace and that growth is also not very inclusive, things start to break. They break economically, they break socially, they break politically, and they break financially. In order to say that the New Normal will last another five years, you have to say that these breakages won’t matter, but they do matter.”

Hence, a flat yield curve can be seen as a yardstick of ineffective policy normalization focusing on the “wrong part of the term structure.” This phenomenon is far from cost-less, for there are financial, social, and political stability implications.

Disclaimer: not investment advice.

Next article12 04 2017 | by Victor Xing | Central Banks